My biggest enemy is my inability to finish projects that I start. My professor just pointed this out to me recently, but I’ve known this my entire life.

Why does this happen?

The common theme is that I lose interest, but there are so many underlying reasons for this loss of attention, including:

1. The impetus for beginning the project is no longer relevant. For instance, the emotions behind the main theme of a song or a story no longer matches how I am feeling.

2. My skills improve over the course of working on the project, and the initial work is no longer satisfying and would need to be redone to a higher standard. This especially applies to visual arts, because my skill continues to change significantly day to day in contrast to my compositional style or writing style.

3. The project was too ambitious, and it turns out to be beyond my skill level to complete the project as originally envisioned. Sometimes, time can correct this issue.

4. Something new is more interesting and distracts attention.

5. The project involves a lot of repetitive actions which get boring. This is particularly true of art projects, where tasks like drawing forests or large bodies of water can simply become tedious.

6. Completion anxiety. I don’t know how to really describe this, but this is a fear of finishing a chapter of my life, of closing off a story thread and letting it slowly drift into the past.

Why is it so hard to go back and finish things?

The task of resuming an abandoned / on-hiatus project becomes more and more difficult with time. In general, it’s easiest to resume a writing-only project, provided that a few pages have been written: first, the software doesn’t change rapidly, and text / document files are generally openable in a number of redundant programs; second, while writing style varies from story to story, the language and vocabulary are essentially the same; and third, I tend to leave enough character sketches and descriptions, and plot pointers, to suggest what needs to be done.

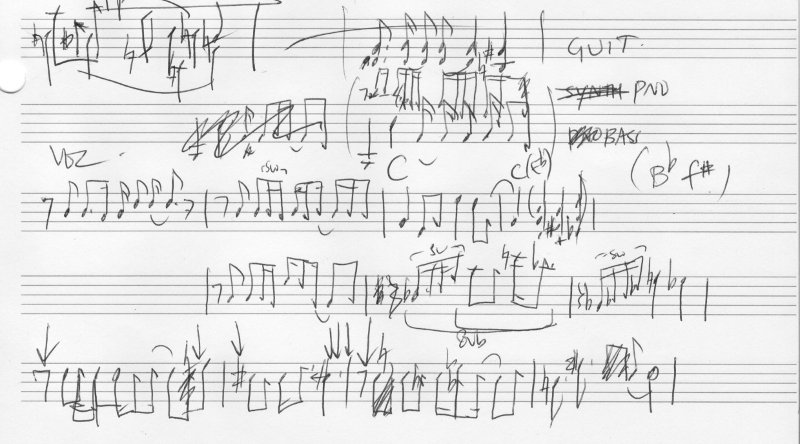

Resuming a musical project is much more difficult. In this case, there are frequently software compatibility issues. I have used Rhapsody, Finale 2003, Finale 2008, and Finale 2012 to compose, and in addition to not being back-compatible, forward-compatibility is also limited. Rhapsody files can be read in 2k3 and 2k8, but with incomplete information – tempo changes, dynamic changes, playback channels, and some transpositions (for transposing instruments) are lost – and into a Finale format with missing expression palettes. Combined with the need to reassign all channels and convert to VST playback, this can be almost as much work as starting input from scratch. Rhapsody files can’t be read into Finale 2012 at all. There are also stylistic issues: my musical preferences change rapidly, and I do not necessarily retain the skills for writing in a particular style after moving on. This makes for a high chance of a disjointed transition from old to new material, for instance in how the development of a theme unfolds.

Resuming an artistic project suffers primarily from rapid growth in skill. Use of the wrong brush settings in an old artwork can be very frustrating to overcome, because touching up line-art is as difficult if not more difficult than creating new line-art. Old poses and expressions can also be off on second glance, and rotating a face by 5 degrees in three dimensions is nearly impossible without complete re-painting. While overall skill level improves, there may be missing information about past settings (e.g. the method used to create meshes in 3D, or a particular custom brush used to create an artistic effect or pattern) which prevents continuation of an incomplete portion of a larger region in the work.

Finally, resuming a scientific project is plagued with incomplete information – missing documentation of previous experiments with important data; experiments performed by people no longer in the lab; lack of reagents from the same batch or even complete inavailability of the reagent altogether. It is often difficult to restart pipelines to plug in holes that become apparent in hindsight. Use of proprietary software formats can make data impossible to retrieve and re-analyze if done improperly the first time around, and programming code can be hard to decipher if poorly commented or written by someone else.

What I want to do about it

Leaving masses of unfinished work takes a psychological toll – each “open file” requires a working memory of present status, and an internal to-do list provides automatic reminders. This becomes unbearable when the magnitude gets too large and a significant portion of ‘brain cycles’ are consumed for reminders and maintaining a fresh memory of works in progress. Flitting from one idea to the next means that nothing will ever get done, as attention and time become divided into unsustainably small quanta that aren’t large enough to make any progress.

The solution is to release such unfinished tasks, either by definitively abandoning them or completing them. My priorities for finishing are the following:

Writing:

I have countless unfinished stories. But ones with only a page or two and generally unsalvageable – there’s not enough plot and characterization to go off of. The two most important stories that I’d like to finish are the episodic “La Petite Princesse,” a series of tales in the same style as “The Little Prince,” but exploring modern allegories; and second, “Andromeda,” a story near and dear to my heart about a boy who wants to change, as told from the point of view of his twin sister.

Art:

Nisuna and Faxuda portrait in front of a tree (very nearly completed)

Andromeda and Irene’s portrait (3/4 completed)

Angel’s portrait (draw it again – 2/3 completed)

Music:

Trio for Flute, Violin, and Piano (3/4 movements completed)

Violin Concerto No. 60, 2nd movement (tutti and main solo theme written)

Games:

Tales of Graces f (now completed)

Final Fantasy XIII (final chapter)

Disgaea 4 (final stage, I believe)

Atelier Totori (final arc – building the ship to find Totori’s mother)

Scientific Projects:

Communicating nanoparticle project

Lung tissue engineering project

Anticoagulant nanoparticle project